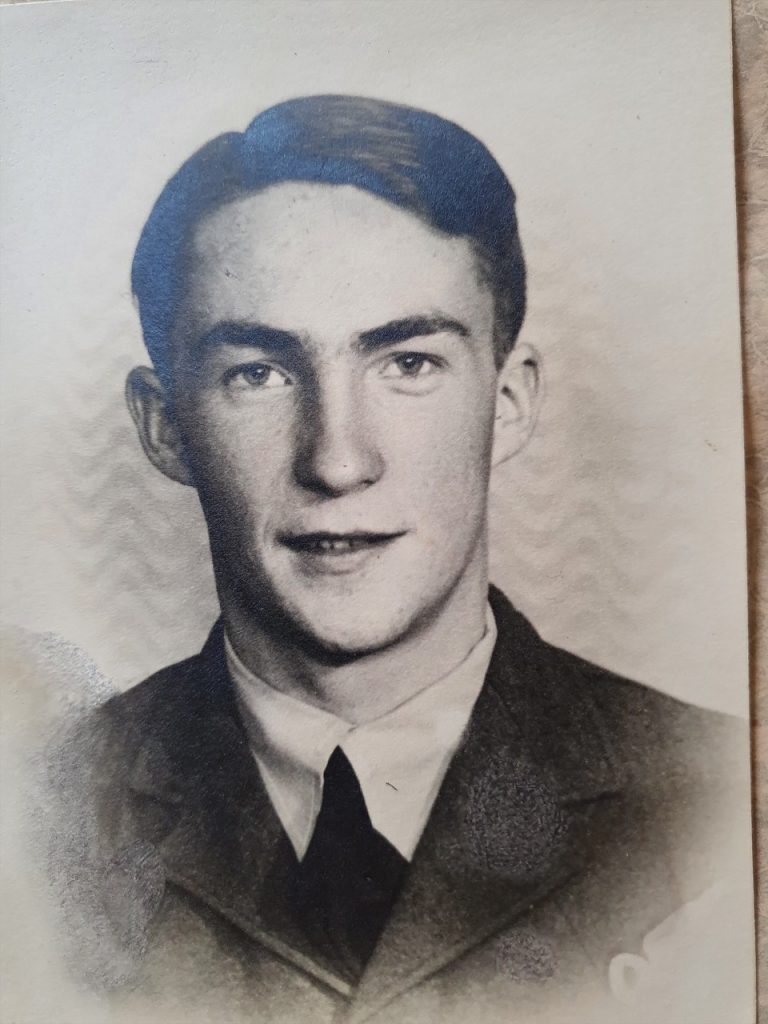

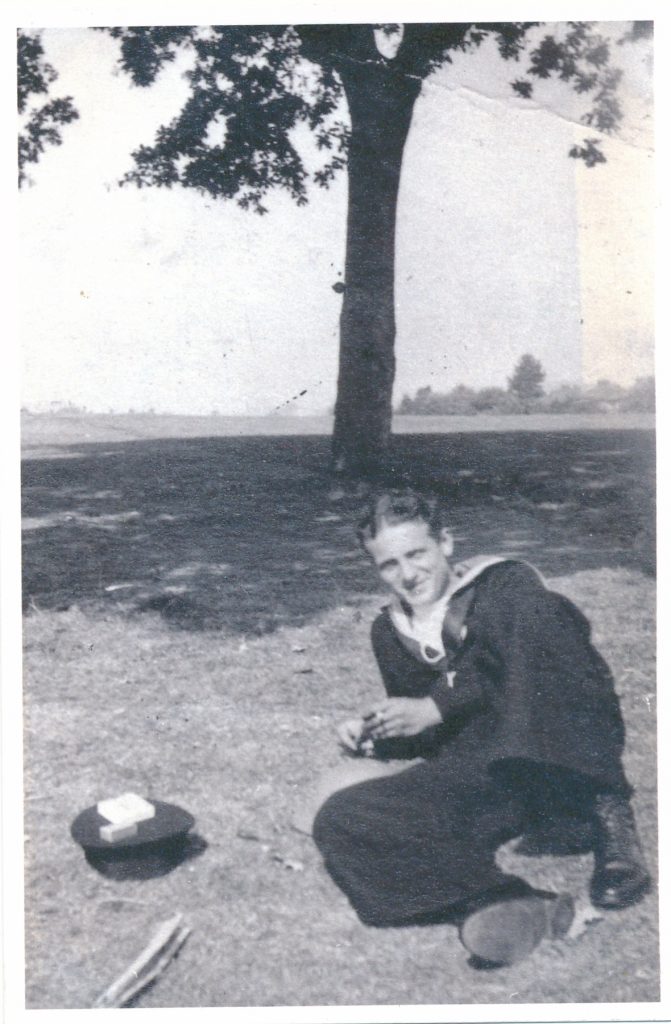

Ernest John Squires, the son of a real life Kelly blaster, was born at 5 Lower Brookfield. He showed great academic promise, gaining entrance to Newton Abbot Grammar School but his consuming ambition was to join the Royal Navy which he achieved aged sixteen in 1936.

In 1941, Ernie was crew on HMS Stanley, one of the many US destroyers Britain had received in exchange for bases in the West Indies. That December, it was part of an escort group spearheaded by Commander F.J. Walker, an anti-submarine specialist eager to deploy tactics which he felt would give them the upper hand – tactics, indeed, which would subsequently become standard practice.

When the convoy set sail, it comprised 31 vessels, a huge armada which would have spread out across some 30 square miles of open sea. They were shadowed, from the outset, by a pack of U-Boats.

During their journey, there were many encounters and many successes. But there were losses on our side too, including HMS Stanley which was struck by a torpedo causing a massive explosion killing all but 25 crew. Ernie was not one of the lucky ones. He is commemorated on the Naval Memorial on Plymouth Hoe.

A more detailed biography can be found in the Lustleigh Society’s new book “Home Front to Front Line” which recounts various aspect of the village during WW2 and is available from The Dairy, the Archives and at Lustleigh Society events.

On Friday 19th December 2025, Lustleigh Bell Ringers will sound a half-muffled peel in his honour.